“Plutocratic Insurgency Note No. 7 – Profit Optimization Beyond ‘the Invisible Hand’”

There is an enjoyably agitated article in the online ‘Small Wars Journal,’ with the title “Plutocratic Insurgency Note No. 7: Artificial Intelligence (AI) Pricing Software - Profit Optimization Beyond ‘the Invisible Hand.’” The subject is the growing ability of corporations to squeeze more profit out of online customers, by using ‘big data’ to charge different people different prices for the same product, according to their ability to pay.

There is an enjoyably agitated article in the online ‘Small Wars Journal,’ with the title “Plutocratic Insurgency Note No. 7: Artificial Intelligence (AI) Pricing Software - Profit Optimization Beyond ‘the Invisible Hand.’” The subject is the growing ability of corporations to squeeze more profit out of online customers, by using ‘big data’ to charge different people different prices for the same product, according to their ability to pay.

“Thousands of large businesses and multinational corporations are now getting a ‘helping hand’ from the use of artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms linked to big data pools that draw upon customer tracking software and real time market pricing and sales updates. These algorithms allow for corporations to engage in the additional extraction of anywhere from a few pennies a gallon for gasoline through to hundreds of dollars for large consumer goods or airline flights during each customer transaction…

"Artificial intelligence employed as a form of ‘subtle e-market strong arming’ that squeezes additional profits out of unsuspecting consumers represents a far cry from the spirit of free market capitalism discussed in Adam Smith’s 1776 work The Wealth of Nations. A 21st century revision of the work would now be more in line with the concept of the wealth of corporations benefiting their plutocratic elite shareholders. In the predatory—extra-sovereign—capitalist economy that is emerging, individual consumers have become ‘marks’ to be shaken down by transnational corporations for the last pennies in their pockets as part of their initiatives towards profit optimization.”

Perfect price discrimination

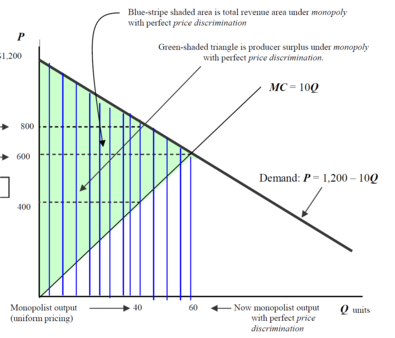

Although the authors do not use the term, the monopolistic behavior they describe is well known to economists as ‘perfect’ or ‘first-degree price discrimination.’ In the model of a competitive market, firms charge a single price. Many customers enjoy a consumer surplus, because, at that price, they pay less than what they would have been willing. A perfectly price discriminating monopolist, on the other hand, knows enough about each customer to charge them a different price, according to their maximum willingness to pay. In theory, the level of output will be the same as in a competitive market, but the distributional outcome is different: the monopolist drains off the consumer surplus. Shareholders, managers and other 'stakeholders' in the monopoly gain at the expense of consumers.

Hal Varian's ‘Intermediate Microeconomics’ textbook is reassuring that perfect price discrimination is an idealized concept, with few real-life examples. But Professor Varian, who is the chief economist at Google, oddly omits to mention that the growth of internet e-commerce multiplies the opportunities for perfect price discrimination.

Adam Ozimek at Bloomberg notes: “The more information we have, the more profitable first degree price discrimination will be. As big data and online buying increases the information that business have on us, the ease and profitability of first degree price discrimination will become difficult to resist.”

Felix Salmon at Reuters says that: “the obvious place for this kind of price discrimination is newspaper paywalls. The FT [Financial Times] already does it: there’s no real list price for an FT subscription, and the paper basically just charges whatever it thinks it can get away with, given what it knows about you…. And here’s the thing: newspapers know a lot about their readers — and especially the regular readers who come back often enough to hit paywalls. To take a simple example, they know if those readers are looking at local sports reports, or whether they’re looking at general entertainment news. The former group will be much more willing to pay than the latter. But they’re also quite likely to know a lot more about you than that, including — if you’re someone who’s ever had a print subscription — exactly where you live.” Grrrr! I subscribe to the FT. I’m annoyed I probably got suckered.

Here’s a 2015 paper on Measuring price discrimination and steering on e-commerce websites: “we use the accounts and cookies of over 300 real-world users to detect price steering and discrimination on 16 popular e-commerce sites. We find evidence for some form of personalization on nine of these e-commerce sites. Third, we investigate the effect of user behaviors on personalization. We create fake accounts to simulate different user features including web browser/OS choice, owning an account, and history of purchased or viewed products. Overall, we find numerous instances of price steering and discrimination on a variety of top e-commerce sites.”

Here’s an ‘Econsultancy’ piece with some thoughts on how you might try to combat online price discrimination. Try clearing your cookies and browsing data or swapping browsers and computers. But I have a hapless feeling these Mickey Mouse defenses will probably be as nothing before the sophisticated algorithms of the internet moguls.

Antitrust?

So what about antitrust regulation by the government? There's a good 2017 paper by Ramsi Woodcock arguing for just this: "Price discrimination as a violation of the Sherman Act". To show that online perfect price discrimination violates U.S. antitrust law, you'd need to show, first, that it harms consumers - which seems easy enough - and, second, that the company is a dominant firm which is acting to exclude competitors from its market.

Here's where things get interesting. For a perfect price discriminator its most effective competitors would be some of its own customers. Suppose that less wealthy readers get low price subscriptions to the FT, and can turn around and sell those subscriptions on an online secondary market. Any price discrimination scheme would collapse.

To stop such arbitrage, online price discriminators have to stop customers from reselling the product, for example by writing a promise into the contract of sale - and that would be exclusionary conduct, coming under the ambit of the antitrust laws.

Here's what you read on the FT's 'Terms and Conditions' web page, for example: "Each registration is for a single user only. On registration, you will choose a user name and password (“ID”)... You are not allowed to share your ID or give access to FT Content through your ID to anyone else... You may not create additional registration or subscription accounts for the benefit of others or with the aim of avoiding our use of IDs to control access to and use of FT.com."

Ramsi Woodcock discusses several remedies, such as enforcing freedom to resell the product, but concludes that the best remedy would be a uniform pricing rule: the firm can choose any price it likes, but it must be one price for all customers.

We'll have to see if the putatively populist Trumpians get any tougher on anti-competitive conduct than the Obama administration. But here's a 2015 report by the Obama White House on “Big Data and Differential Pricing” that is remarkable for its generally sunny lack of concern over these phenomena, and emphasis that existing consumer protection laws will be quite enough to handle any future difficulties. The term 'antitrust' is used not once! No worries there for our good friends in Silicon Valley.